Brokeback Mountain

Official Brokeback Mountain Site

Official Brokeback Mountain SiteDrama/Romance

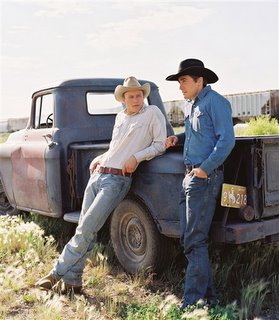

Starring Heath Ledger, Jake Gyllenhaal, Randy Quaid, Anne Hathaway, Michelle Williams

Rated R (for language, some strong sexual content/brief nudity, mild violence)

Running Time: 134 Minutes

Released:December 9th, 2005

2 Out Of 5 Bites

The affair that begins furiously on that thar Brokeback Mountain is a daring, but pitifully pretentious parade of a selfish gay affair that banks our emotional sympathies upon the star-crossed lovers' tragic attempts to validate their hidden relationship. As a down-payment, it could be argued that we are asked to suspend the moralizing and coalescing around any valuation of the "traditional" family makeup of a man and a woman (and all the other ways the arguments are made for "normative," heterosexual, monogomous relations between a man and a woman in the context of marriage).

But, director Ang Lee's take on Annie Proulx's short story seems not to be suggesting that anyone suspend such valuations, which, inherently, might be the problem.

The 1963 Wyoming, in which the film opens, is a scenic monument and Lee superimposes the gay fling over that big sky as if to beg an analogous equality therein. The reserved Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) shows up at a rancher's headquarters just ahead of Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal), who already looks as if he's up to something. Both are looking for summer work and they find it as sheepherders. In due time and owing some thanks to some whiskey and frigid temperatures, Twist and Del Mar consummate their physical interests and desires that mask their stunted emotional selves.

Twist seems to be the initiator, having passed numerous, longing looks toward the bumble-mouthed Del Mar that unabashedly foreshadow his intentions. When Twist makes his move, Del Mar appears somewhat upended, but, proving to be no victim, he becomes the aggressor. Del Mar insists to Twist that this is a one-time deal since he (Del Mar) is to be married in short time.

Neither Del Mar nor Twist were interested in the most obvious "right" thing to do, given the fact that their hot submission to their passions were to affect many more lives in irreversible ways. In one fail swoop of compromised sobriety, judgment and sexual libido, they give in to that which they think they deserve to afford themselves, and it is actually the very thing that robs them of fulfillment.

The devastation of the secret relationship, once discovered, is rampant in it's destruction on both men and the women they would later marry and the children they would father. The willingness they both have in continuing the deception is highlighted, but confusingly so, because it simultaneously comes off chronicling the debaucherous affair in a frolicsome pitch that should have been reserved for the marriage relationships into which they both entered while painting a picture of the relational fractures without a meaningful congealment in the end. It is a tragedy for tragedy's sake that doesn't harbor a worthy commentary against the chain links of their adulterous liasons as much as the film argues for why both men's relationship was a just one from the beginning. The effectual perspective, then, is that the real downfall was that they didn't stand up to their fear and the conventional, pervasive public opinion (real or perceived by them) and, in so doing, consequently go ahead with their outwardly gay relationship.

After a four-year hiatus from one another, Jack descends into the life of Del Mar again, who doesn't really seem to be hacking it too well as a rancher, father and husband. He is his backward self, but doesn't really seem to come to life until Jack's correspondence, which begins several more years of rendezvous under the guise of fishing trips.

They analyze their dead-end lives they have willingly entered into and wrestle with their reasons for not having gone off on their own together from the beginning, which only stirs up emotional strife between the two. Twist, during a heated argument between them on one trip, bemoans, "I wish I knew how to quit you." This has less the import intended if one looks at the fact that their place is one of their own choosing. As such, it becomes a laughable tag line for what the film hoped would have been an instrument endearing some to the lover's plights.

But perhaps that is the (minimally) effective tragedy of Lee's film; these two had no frame of reference for making responsible choices regarding intimate relationships, especially relationships that circulate around dominant male-figures in their lives. Del Mar recounts how, as a child, his homophobic father took him to the place of a murder scene where a gay cowboy was mutilated. Twist is depicted in constant adversarial positions with his father-in-law until he finally stands up to the "ignorant s.o.b." (in as many words) at a Thanksgiving dinner, no less.

This is not the typical romantic, angst-ridden story-telling vehicle with which we have been sold, considering the hype surrounding the film. At times, their relationship has much less to do with "romance" than it does with the way the film relishes in it's ability to display its homoeroticism- sometimes bluntly, sometimes subtly- but overpresent nonetheless. The performances are quirky, with Ledger's Del Mar being the most memorable, even if his dialect is hard to understand, sounding at times as if he is speaking through cotton balls in his cheeks, a la Marlon Brando. Gyllenhaal's Twist is much less believable, overposing in scenes as if to propose the new gay cowboy image. At least with Del Mar, there is a deepened mystery of character underlying what we see and what we wish we could see, but Gyllenhaal's depth is truncated by one or two shout-bursts from what is otherwise just a linear performance.

Michelle Williams plays Del Mar's wife, who inadvertently discovers her hubby in a lip-lock with Twist. The movie props itself upon her inability to confront her adulterous husband while continuing to compare it to the descent of Twist into the other sexual dalliances south of the border from his home in Texas, consistently consigning his family to wandering around in an emotional aloofness. Randy Quaid as Del Mar and Twist's boss is a mentionable performace as one might expect from Quaid, here, the dead-pan, no-nonsense cowboy businessman who discovers his hired help have other interests.

The picture is an ongoing highlight of the continuance of their affair, while building up to some sort of climactic ending to the forbidden relationship (tritely alluding to the Matthew Shepherd case a few years back). The way the relationship is resolved, if it is, is not from the place of maturation in light of the pain caused in their taboo endeavors, but from the grief of their own loss and what could/should have been. Neither man develops positively, but they only deepen in their downfall, having been solidified in character bit by bit by the decisions they made along the way.

The film may break ground in the genre available with which the homosexual movement has to depict its issues, assuming that is their perspective. In avoiding its own stereotypes pronounced an anathema in our socio-political climate, it blindly enters into cheap portrayals of Texans as poorly dressed, dim, dull and tacky. Wyomingans are pallid, uninteresting and liable to be mistaken for walking stiffs.

Brokeback is not lacking in cinematography or guts. It might even excel in portraying some levels of human fallenness. But it certainly offers nothing freeing and redemptive in the stead of the massive human relational casualties it contains. It will alienate some who see it as a new step in an agendized arts climate and endear itself to others looking for a more empathic voice in cinema for sure, but it certainly has not warranted the adulation of the Hollywood elite for refreshment in filmaking. It breaks new ground in its brashness, but thematically, it tends toward predictability and washes up generally trampled in an over-hyped critical stampede.

<< Home